1. Objectives of the Evaluation

This report presents the results of the evaluation of the processing component of the Library and Archives Canada (LAC) Acquisition and Processing of Private Archives Program (APPAP). The evaluation assessed the program’s performance over a 5-year period, from April 2015 to March 2020, and addressed the following questions:

- To what extent are the internal policies, procedures and service standards adhered to during the processing of private archives?

- How efficient is the processing of private archives at LAC?

- What progress has been made in attaining the short- and medium-term program results to which the component contributes?

2. Program Description

2.1. Acquisition and Processing of Private Archives Program

APPAP is part of LAC’s core responsibility: Acquiring and preserving documentary heritage. The Archives Branch administers the program. The Branch is responsible for documenting the evolution of Canadian society through identifying, evaluating, acquiring and processing government and private archives. Two divisions within the Branch carry out the acquisition, processing, description and specialized reference of private archives, namely:

- The Science and Governance Private Archives Division, which is responsible for private archives from the economic, scientific, political, administrative and military spheres of Canadian society; and

- The Social Life and Culture Private Archives Division, which is responsible for private archives from the social, cultural and artistic spheres of Canadian society.

For simplicity’s sake, the term “LAC’s Private Archives” (LPA) will be used to jointly refer to the above divisions throughout the report.

The Circulation and Physical Control team and the Digital Integration team from the Digital Operations and Preservation Branch are also involved in certain aspects of archival processing. Their responsibilities in this regard are the following:

- Ensuring physical control and proper tracking of LAC holdings through the different stages of processing, including inventories and audits;

- Planning and managing collection spaces, archival housing, and archival supplies;

- Managing the physical transfer and intake of archival records to LAC custody;

- Implementing the physical disposition of records deemed not to have archival value; and

- Defining, managing and supervising all procedures and operations related to pre-ingest of all digital archival records.

Footnote 1

2.2. Private archives processing workflow

According to the literature, archival processing is the means by which an institution gains physical and intellectual control over documentary heritage material it has obtained through donation, purchase or transfer. Archival processing involves the arrangement and description of archival material to prepare it for access and long-term preservation. An institution’s internal policies and guidelines serve to define the criteria and standards for determining the level of arrangement and description of its archival fonds. There are a number of factors to take into account in processing an archival fonds:

- internal policies and guidelines,

- the research potential of the collection,

- the original order and the physical condition of the material,

- the number of full-time equivalents (FTEs) required / available for processing,

- the format of the material (such as oversized items, audio-visual material, electronic records),

- the nature and complexity of the activities documented in the fonds,

- the donor’s specifications (if any) in the deed of gift, and

- any access restrictions relating to sensitivity or security requirements.

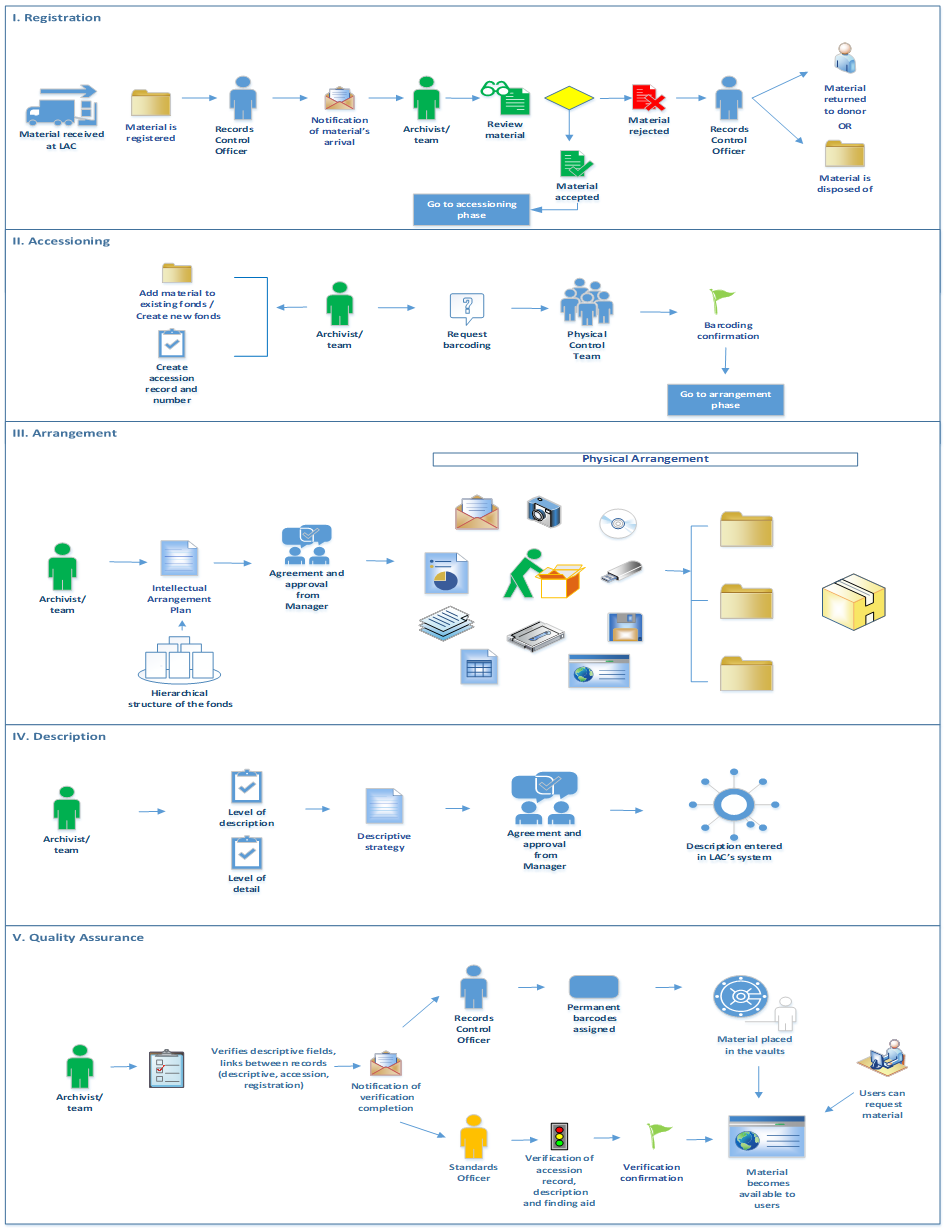

At LAC, processing refers to the physical processing and intellectual arrangement of archival material. Physical processing is carried out at the accessionFootnote 2 and description stages in the life cycle of archival records. It involves the physical arrangement and housing of a collection, and takes into consideration the physical format, size, media (including the environmental requirements of media), and access restrictions.Footnote 3 Intellectual arrangement involves making decisions regarding the interrelation of records and their groupings, while attempting to maintain or reconstruct the original order of the records as they were created or accumulated by a fonds’s creator.Footnote 4 The program’s documentation identifies the following stages in the processing workflow: registration, accessioning, arrangement (includes intellectual and physical control), description, and quality assurance.Footnote 5

Archivists are responsible for processing material for the specific fonds or collection to which they have been assigned.They work in close collaboration with staff from the Physical Control and Quality Assurance teams, who assist with intellectual and physical arrangement planning, provide archival supplies, and offer preservation advice.Footnote 6

LAC follows the national standard for the description of archival material, “Rules for Archival Description” (RAD),Footnote 7 developed by the Canadian Council of Archives, and its own internal standards, procedures and workflows.

2.3. Program resources

The financial and human resources allocated to LPA are presented in Table 1 for information purposes. It should be noted that, prior to 2018, LPA and Published Heritage were part of the same Documentary Heritage Program under the former LAC Program Activity Architecture. Following the introduction of the Treasury Board Policy on Results in 2016 and a 2-year transition period, the two programs became separate entities. Therefore, the data for 2015–2016 to 2017–2018 represent the common resources for the former Documentary Heritage Program, and the data for 2018–2019 to 2019–2020 represent the resources for LPA as a stand-alone program. It can be observed that, while the financial resources have remained relatively stable throughout the period under review, human resources display larger fluctuations. Internal restructuring and other internal constraints explain that trend.

Table 1: Program Resources

| DescriptionFootnote * | Fiscal year |

|---|

| 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 |

| Program funding (in Canadian dollars) |

|---|

| Planned spending | 11,591,441 | 13,095,854 | 9,649,880 | 7,221,145 | 8,286,743 |

| Actual spending | 12,999,827 | 6,273,602 | 5,873,679 | 6,483,844 | 7,745,453 |

| Total LAC spending | 91,451,612 | 114,500,637 | 127,416,749 | 124,630,164 | 134,354,195Footnote 8 |

| Percentage of program spending as part of LAC’s total spending | 14.21% | 5.48% | 4.61% | 5.20% | 5.76% |

| Human resources (in full-time equivalents – FTEs) |

|---|

| Planned FTEs | 130 | 142 | 112 | 83 | 88 |

| Actual FTEs | 165 | 76 | 98 | 77 | 89 |

*Spending includes salaries and other operating costs

Return to footnote * referrer

Table 1 - text version

Table 1 presents the program’s resources for the 2015–2016, 2016–2017, 2017–2018, 2018–2019 and 2019–2020 fiscal years.

3. Methodology and Limitations of the Evaluation

The evaluation was conducted in accordance with the 2016 Treasury Board Policy on Results and Directive on Results, including the evaluation standards described therein. The evaluation used a mixed-method approach, combining qualitative and quantitative lines of inquiry, including a document and literature review, key informant interviews, an employee survey, and analysis of financial and performance data.

Limitations in the literatureFootnote 9 and in the performance metricsFootnote 10 used by the program did not allow conducting in-depth efficiency analysis and assessment. To compensate for that, the evaluation gathered supplementary data through key informant interviews, an employee survey, and a document review.

4. Evaluation Findings

4.1 Awareness and application of LPA’s policies, procedures and service standards

Finding 1: Not all internal policies, procedures and instruments related to processing are up to date. In addition, the roles and responsibilities for revising them are not clear.

Interviews and staff survey data indicate that not all internal policies, procedures and service standards related to processing are up to date and that some have not been revised in the past 5 years or longer. Furthermore, the staff survey indicates that 37% of respondents do not believe that LAC’s policies, directives, workflows, procedures, service standards and guidance materials related to the processing of private archives are up-to-date. In addition, 14% are not aware if the policy suite is up-to-date, and 49% feel uninformed about updates made to the policy suite as a whole.

According to management, lack of resources and other contextual factors have limited LPA’s ability to keep these current.

As regards the roles and responsibilities for revising and updating policy instruments, LPA has put in place a new practice whereby it convenes a working group on an annual basis to prepare a three-year policy renewal plan. The working group has rotating membership from private archives staff and is chaired by a director. However, interviewees appear to be unaware of this practice, as some ascribed the responsibility for revisions to the Control Committee, others to the Strategic Research and Policy team or the Quality Assurance team.

Finding 2: Processing service standards are not widely used by staff, and adherence to them is not actively monitored.

The document review and the interviews revealed that LPA began reviewing its policies and procedures in 2015. Working groups were created and tasked with exploring ways of improving the efficiency of processing. Pilot projects were carried out, and further analysis of the results is expected to take place in 2020–2021. Interviews indicated that the incentive came from the Director General (at the time) and the management team, who wanted to ensure that archival processing is done within reasonable timeframes and that incoming material is described in a way that allows optimal accessibility. Specifically, they wanted to ensure that time-consuming and resource-intensive detailed descriptions and processing are done only when appropriate and after proper justification has been provided.

The report of the Working Group on Selection, Arrangement and Description of Private Archives (2015) revealed that:

- LAC was not as efficient as it could be in processing and describing fonds;

- Custodial archivists did not have time to address persistent description issues and gaps or to meet research needs; and

- Staff were unaware of processing service standards.

In the course of their work, the working group also found that, on average, acquisition and processing activities were taking from 51 to 122 days and that staff were inconsistently tracking case complexity, which inhibited the ability to efficiently measure compliance with service standards.

Among other things, the working group recommended the implementation of physical and intellectual arrangement standards that are flexible, take into account different media types and client demand, and encourage minimal processing, as appropriate. According to the working group, such an approach will help prevent excessive description and will be beneficial to both staff and researchers. In addition, the working group recommended that processing service standards have to be communicated more effectively to archival staff and that compliance with the standards should be encouraged.

The service standards for private archives processing are documented in LAC’s Archival Collection Management Reference Manual and the archival control system MIKAN. These service standards are based on the priority and level of complexity of the material (see Table 2 below).

Table 2Footnote 11: Service Standards

| Level of priority | Complexity |

|---|

| Simple | Medium | Complex |

|---|

| Urgent (Current FY) | 1 month | 3 months | 9 months |

| High (Next FY) | 12 months | 15 months | 18 months |

| Medium (Next 2-3 FYs) | 24 months | 30 months | 36 months |

| Low (Next 4-6 FYs) | 48 months | 60 months | 72 months |

Table 2 - text version

Table 2 presents the service standards for the processing of private archives by level of priority and level of complexity.

Interviewees were unable to recall or define the processing service standards. For example, some stated that a simple case takes 3 months, while others specified that it can take up to a year, or that the standards were 3, 6 and 12 months depending on the size of the fonds.

Few interviewees indicated that they actually monitor the time that processing takes and that, in practice, strict adherence to the service standards is not always possible due to issues related to the complexity, condition and volume/extent of the material. Furthermore, some interviewees indicated that the decision to develop the service standards was made without involving the managers in the process.

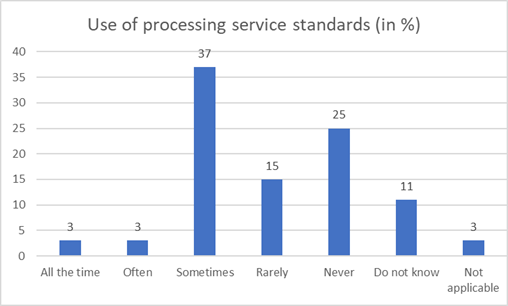

The staff survey further demonstrates that, while staff are aware (73%) of the standards, they are not actively using them. The data in Figure 1 indicate that only 3% of respondents use LAC’s processing service standards all the time, compared to 37% who use them sometimes and 25% who never use them.

Figure 1

Figure 1 - text version

Figure 1 presents data on the percentage of employees who use processing service standards.

| | All the time | Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | Do not know | Not applicable |

|---|

| Processing service standards | 3 | 3 | 37 | 15 | 25 | 11 | 3 |

|---|

Moreover, 60% of respondents feel uninformed about updates made to the processing service standards. In addition, 37% do not feel actively consulted about changes made to the standards, and 34% believe their feedback regarding changes to the standards is not taken into consideration.

Finding 3: Practices to ensure that policies, procedures and service standards are followed and applied throughout LPA are inconsistent.

Interviews indicate that the program’s management rely on the Quality Assurance team for ensuring coherent and consistent application of policies, procedures and standards, and on the Control Committee for the monitoring, revision and updating of procedures and instruments. However, they also revealed that managers have varied practices for ensuring that policies, procedures and service standards related to processing are followed and applied. For example, some place more emphasis on continuous training and competencies development, while others have established specific processing practices or targets (such as one box per day per employee or processing three days per week). In addition, certain managers appear to rely on the Quality Assurance team or the general process in place that requires managers to review and provide approval at several points throughout the course of processing.

According to the LAC Archival Collection Management Reference Manual, managers are solely responsible for monitoring adherence to the service standards,Footnote 12 while standards officers from the Quality Assurance team are responsible for ensuring that staff are “informed on established standards and rule interpretations and for authority control relating to fonds, collections, single and discrete items.”Footnote 13 In addition, interviews with the Quality Assurance team revealed that it performs verifications at distinctive points in the process (accession, description and finding aid) but does not monitor adherence to the service standards.

4.2 Efficiency

Finding 4: Processing efficiency as described in the literature differs from how the program’s staff and management understand and define this concept.

The literature describes efficiency of archival processing mostly in terms of the rate of processing and the size of the backlog of unprocessed material, while taking into account availability of resources (staff and financial), the condition and extent of the material, and the research potential of, and the demand for, the material.

The program’s management and staff, however, define efficiency in slightly different terms. For both groups, the efficiency of archival processing is determined by the availability of resources (FTEs, budget, archival supplies, and processing space); the degree of collaboration with the Quality Assurance, Physical Control and Preservation areas; and the clarity and quality of communication.

For senior management, factors such as availability of equipment (for special media processing), complexity and format of the material, ability to ensure that archivists focus primarily on processing and ensuring a balance between rapidity and quality of processing are also important in determining efficiency. Managers added on to that list the level of organization and physical condition of the material, clear definitions of roles and responsibilities, clear terminology and finding a balance between the varied tasks that archivists are required to perform in the course of their work. Staff, on the other hand, emphasize the importance of having the following: streamlined processes, a faster turnaround time for Quality Assurance, clear priorities and feedback, less focus on perfection, less dependency on other areas (such as Physical Control and Preservation), simple and easy-to-use templates, and sufficient time to process.

Moreover, staff stressed the importance of having clear, complete and up-to-date procedures, accessible to all and followed by all, that cover the entire process and that take into account the requirements for access and preservation.

Finding 5: The processing workflow is not well documented and communicated, resulting in a lack of common understanding of its structure. In addition, solicitation of staff is not well managed, and staff are not clear which work activities are core and which are secondary.

Interviewees indicated that there is no operational definition of processing; however, there is common understanding of the term, based on basic models, standards and principles of archival science. While there appears to be general agreement among management and staff with regard to the starting point for processing, which they identify as the signing of the deed of gift, there is less clarity about its end point. They define the latter as any, or a combination, of the following:

- arrangement and description have been completed,

- finding aids have been prepared and finalized,

- descriptions and finding aid have been entered in the MIKAN system,

- a restricted-access form and a disposition memo have been prepared and signed,

- quality assurance has been completed,

- the material has been placed in proper boxes, which have been labeled and barcoded,

- the material has been placed in the vaults for preservation,

- the public / researchers can have access to the material; that is, they can request and consult it.

In addition, management and staff perceptions of the functioning of the processing workflow differ. While management maintains the workflow has been operating well over the past five years, staff indicate that it is not properly documented and communicated, and some are even unaware that there is a workflow. Staff also indicated that:

- the process is too long and complex;

- quality assurance and physical control are acting as bottle necks and cause delays for example, quality assurance in some cases took up to two years, while physical control is not delivering the material and/or archival supplies in a timely manner;

- many of the tasks are not useful and are questionable, for example the need to systematically replace folders.

Management acknowledged that the workflow could be improved further and that its performance is largely affected by process dependencies with other units such as Quality Assurance and Preservation, and by the accumulation of unprocessed material.

In addition, the perspectives of management and staff differ on the major issues affecting the performance of the processing workflow, as indicated in Table 3.

Table 3: Major issues affecting the private archives processing workflow

| Management perspective | Staff perspective |

|---|

- lack of FTEs

- archival supplies shortages

- availability and management of processing space

- imbalance between main work activities and added activities

- lack of mechanisms to manage solicitation of archival staff

- communication with other units

- lack of clear priorities regarding primary versus secondary work tasks

- work relationship between the Quality Assurance team and archivists

| - lack of clarity on procedures and service standards

- lack of processing space and resources

- lack of guidance, training, equipment and knowledge transfer

- lack of communication between functions and lack of clear roles and responsibilities

- time delays and wait times: for barcoding, verification of physical arrangement and disposition by Physical Control; verification of finding aids by Quality Assurance; and inconsistencies in the Quality Assurance procedures themselves

- not being able to focus on primary work tasks and lack of clarity about which tasks are secondary

- outdated procedures and service standards

- lack of opportunity for staff to provide feedback on, or to question, procedures and service standards

|

Table 3 - text version

Table 3 presents the perspectives of management and staff on the major issues affecting the private archives processing workflow.

Interviews with management and staff surveyed highlighted that staff are unable to focus on processing because they are constantly solicited and as a result of interruptions from special reference questions, time sensitive special requests from senior management, and the preparation of special visits and exhibitions. Moreover, some managers stated that they were unaware of the extent of staff’s solicitation because requests are often made directly to staff and sidestep managers.

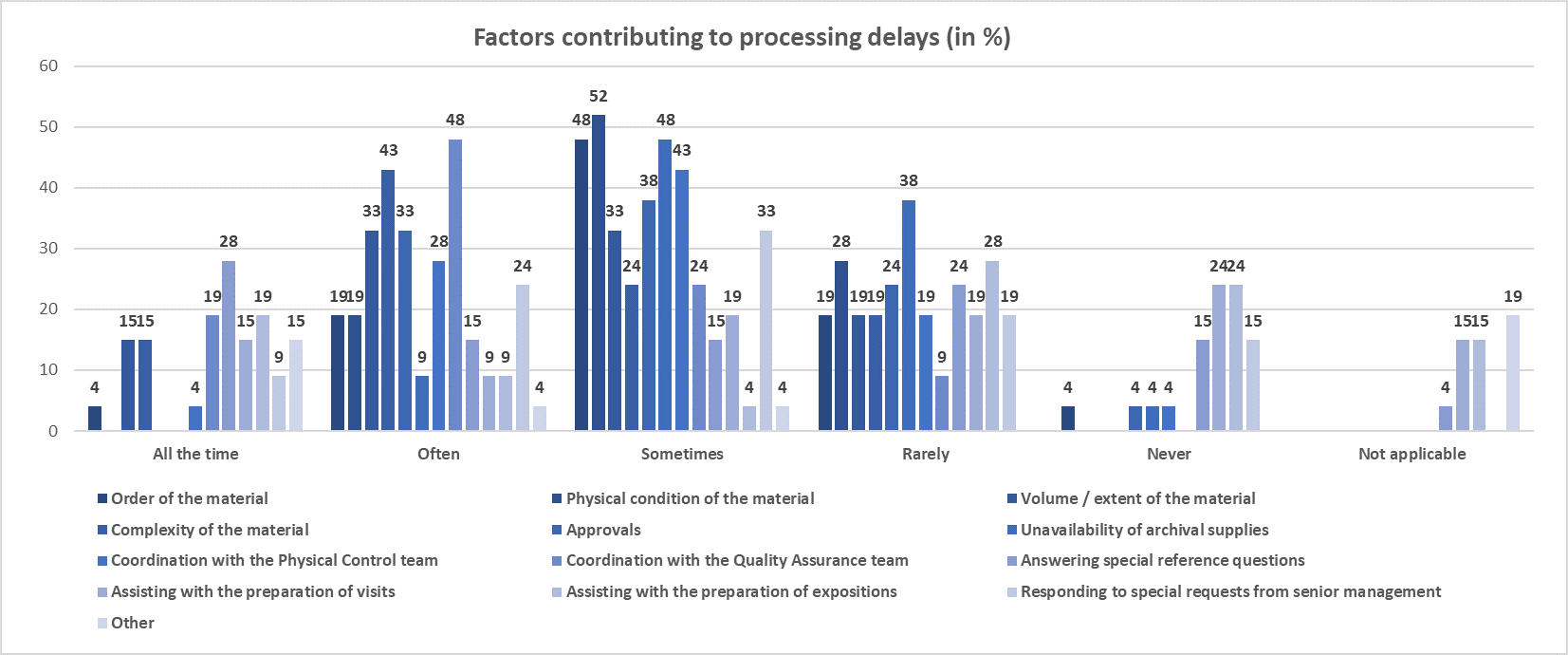

The survey results, however, revealed that some of the issues affecting archival processing are not as prevalent as they appear to management and staff (see Appendix D for full details). For example, the unavailability of archival supplies sometimes (48%) or rarely (38%) contributes to processing delays, while assisting with the preparation of exhibitions (28% rarely, 24% never) and visits (24% never) rarely or never affects processing.

According to respondents, factors causing delays often stem from the complexity of the material (43%) and coordination with the Quality Assurance team (48%), while the factor contributing the most to processing delays is answering special reference questions (28%).

Staff made a number of suggestions for improving the workflow. These are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4: Staff suggestions for improving the workflow

| Workflow element | Improvements recommended |

|---|

| Workflow structure | The workflow should be the same for all media and the standards should be the same for everyone. Processing tasks should be revised with the needs of researchers, not the needs of Preservation, in mind. The workflow should cover the whole process chain and take into account all the elements and all stakeholders in the chain. |

| Procedures and documentation | Steps in the workflow should be simple, logical, sequential, documented and explained. Procedures should be stored in a central location accessible to all staff, updated regularly, and better communicated. |

| Collaboration with other units | The operational efficiency and response times of the Quality Assurance and Physical Control teams in performing verifications must be improved. |

| Approval process | The process is too heavy and too lengthy, for example approvals for simple fonds that do not require a tax receipt sometimes take longer than the actual processing of the fonds. |

Table 4 - text version

Table 4 presents the suggestions from staff for improving the processing workflow.

Finding 6: It is not clear what amount of employees’ time should be spent on processing activities, and managers have hard time ensuring that employees spend enough time on processing.

Program documentation and interviews indicated that FTEs are allocated according to the archival portfolio and field of expertise of staff. Managers create plans for their sections based on the approved acquisition proposals submitted by staff. Estimation of FTEs and archival supplies is typically done at the appraisal stage, prior to the start of processing, and is documented in an evaluation plan. Additional considerations that managers usefor the allocation of FTEs include employees’ workload, the size and complexity of the fonds, the number of acquisitions coming in a fiscal year, and the balance of tasks (for example, blogging, answering special reference questions, assisting with special visits).

Some managers admitted that processing is not a primary responsibility for all staff and that it is challenging to ensure that staff devote sufficient time to processing.

Staff survey data reveal that 57% of respondents devote from 2 to 3 days per typical workweek to processing, 28% devote from 3.5 to 5 days, and 14% devote less than 2 days. The data further show that 50% of respondents typically process 3 fonds or less per fiscal year, including accruals, whereas 24% process from 4 to 6 fonds per fiscal year, and 4% process 7 fonds or more per fiscal year. About 9% of respondents are not aware of how many fonds they process per year.

Finding 7: There is an imbalance in the amount of time and the level of effort that staff dedicate to processing.

According to management, the most effort- and resource- (FTE) intensive parts of the process are the arrangement (including the physical arrangement) and description of the material, because the state of the material and its original order greatly affect its organization and processing. Another important factor is the format of the material, as some specialized media (digital, audio-visual) are more demanding in terms of physical processing and in terms of volume. In addition, staff may need to conduct extensive research on the donors to understand the context of creation of the fonds and the larger socio-historical context, especially in backlog cases.

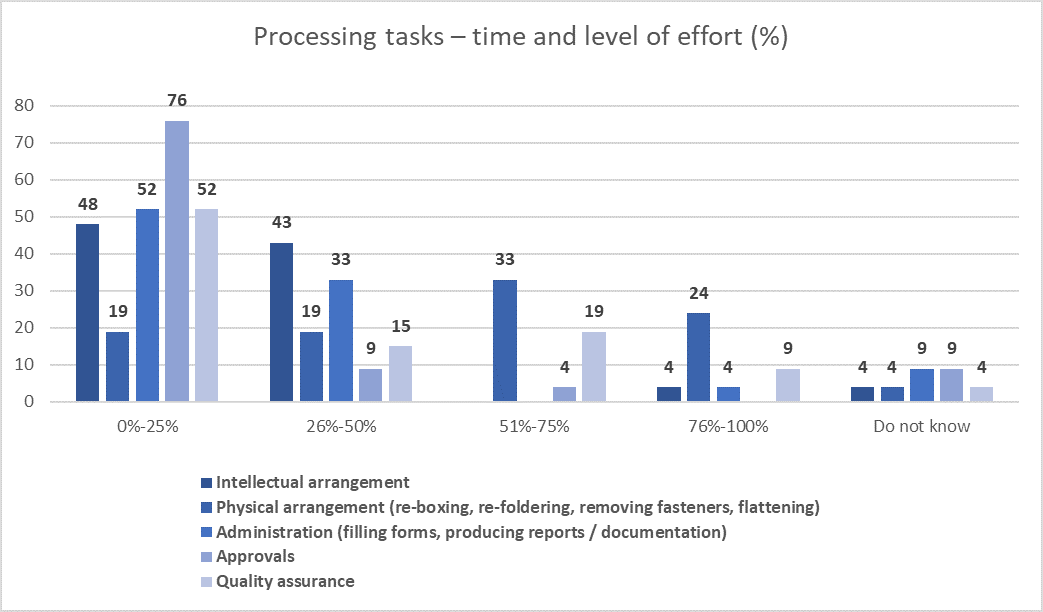

The staff survey data presented in Figure 2 partially confirm management’s perception. The data indicate that the most demanding processing task is physical arrangement: it takes from 51%–75% (for 33% of respondents) to 76%–100% (for 24% of respondents) of respondents’ time and effort. Intellectual arrangement appears to be somewhat less demanding: it takes from 0%–25% (for 48% of respondents) to 26%–50% (for 43% of respondents) of respondents’ time.

Figure 2

Figure 2 - text version

Figure 2 presents data on the time and level of effort that employees dedicate to processing tasks.

| | 0%-25% | 26%-50% | 51%-75% | 76%-100% | Do not know |

|---|

| Intellectual Arrangement | 48 | 43 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

|---|

| Physical Arrangement (re-boxing, re-foldering, removing fasteners, flattening) | 19 | 19 | 33 | 24 | 4 |

|---|

| Administration (filing forms, producing reports / documentation) | 52 | 33 | 0 | 4 | 9 |

|---|

| Approvals | 76 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 9 |

|---|

| Quality assurance | 52 | 15 | 19 | 9 | 4 |

|---|

The survey data also indicate that a higher percentage of respondents concentrate on tasks that take 0%–25% of their time and effort than on tasks that take 51%–75% or 76%–100% of their time and effort.

4.3 Progress in attaining the expected results

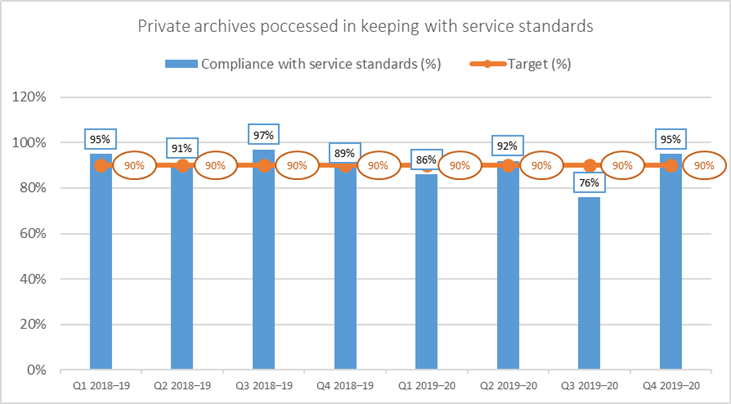

Finding 8: The performance targets for private archives processing for the past two fiscal years have been mostly attained.

The program uses “% of private archives processed in keeping with service standards” as an indicator to measure compliance with service standards. The indicator was introduced in 2017–2018. The baseline was set in the same year, and data collection began in the second quarter. Subsequent targets were set at 90% for both the 2018–2019 and 2019–2020 fiscal years. The data below demonstrate that the performance targets have been mostly attained despites some fluctuations.

Figure 3

Figure 3 - text version

Figure 3 presents the percentage of private archives processed in keeping with service standards by fiscal quarter for 2018–2019 and 2019–2020, and the targets set for those two years.

| Q1 2018–19 | Q2 2018–19 | Q3 2018–19 | Q4 2018–19 | Q1 2019–20 | Q2 2019–20 | Q3 2019–20 | Q4 2019–20 |

|---|

| 95% | 91% | 97% | 89% | 86% | 92% | 76% | 95% |

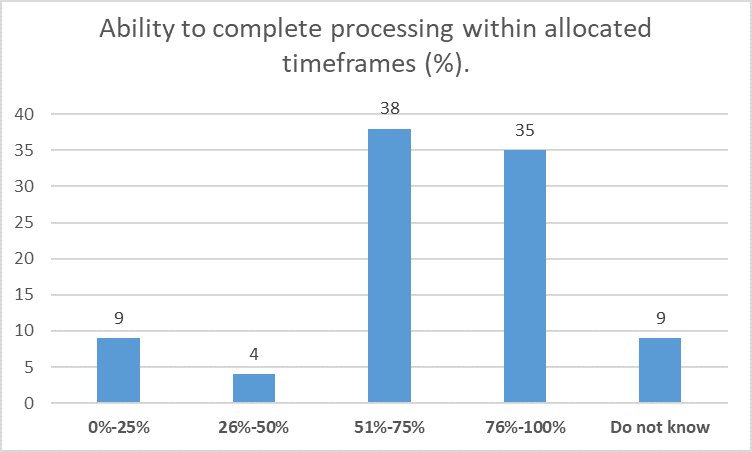

Staff survey data also demonstrate that, in the course of the past 5 years, staff were able to complete the processing of the fonds assigned to them within the allocated timeframes from 51%–75 % to 76%–100% of the time.

Figure 4

Figure 4 - text version

Figure 4 presents data on the level of ability of employees to complete the processing of the fonds assigned to them within the allocated timeframes. Data are presented in percentages.

| 0% to 25% | 26% to 50% | 51% to 75% | 76% to 100% | Do not know |

|---|

| 9 | 4 | 38 | 35 | 9 |

Finding 9: There is a sizable amount of unprocessed material accumulated from past years, and LPA has taken measures to address the issue. Although the proportion of that material is low, compared to total LPA holdings, it is inaccessible to Canadians and its long-term preservation is at risk.

Interviews and document review indicated that there is a sizable amount of unprocessed material, which is not accessible to Canadians. Part of that material accumulated historically while some is more recent. According to interviewees, the backlog has been relatively stable over the past five years. The document review shows that the current size of the backlog is 27,799 containers (as of February 2020). Of those, 7,585 containers are recent backlog (2015–2019), 15,862 containers originate in the period from 1998 to 2014, and 4,352 containers comprise the historical backlog dating prior to 1998. On that basis, the documentation estimates the backlog as an average 0.9% since 2016. When the number of containers in the backlog is converted to kilometres, it represents 8.34km of material, which is low when considered in proportion to the total LPA holdings of 170.167 km (as of May 2020). Nonetheless, the material in the backlog remains inaccessible to Canadians and since it has not been processed, there are risks to its long-term preservation.

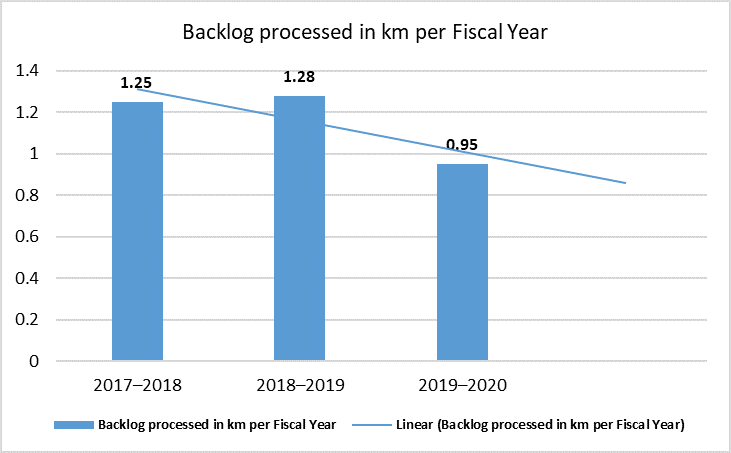

According to LAC’s Departmental Results Framework (DRF), the program has processed 1.25 km of backlog material in 2017–2018, 1.28 km in 2018–2019 and 0.95 km in 2019–2020. The DRF data demonstrate that the amount of backlog processed per year is decreasing (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Figure 5 - text version

Figure 5 presents data on the amount of backlog processed per year for the 2017/2018, 2018/2019, and 2019/2020 fiscal years. Data are presented in kilometres.

| Fiscal Year | Backlog Processed in Km per Fiscal Year |

|---|

| 2017–2018 | 1.25 |

| 2018–2019 | 1.28 |

| 2019–2020 | 0.95 |

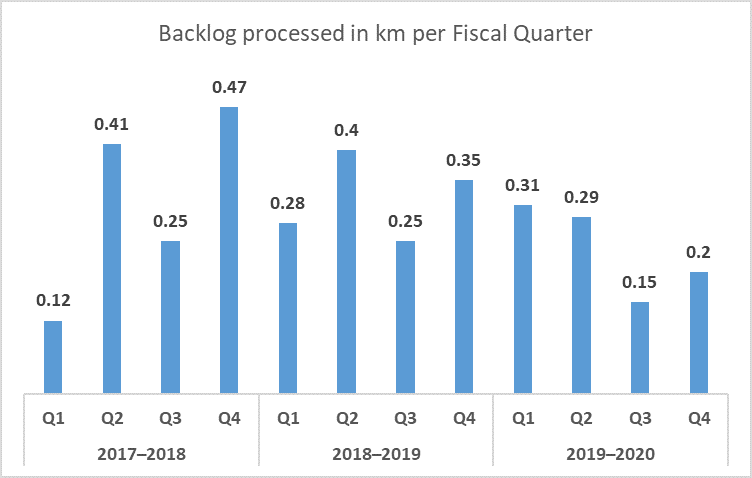

The data also demonstrate that there is a variation in the amount of backlog processed from quarter to quarter, which indicates that the processing of the backlog has not been managed consistently (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Figure 6 - text version

Figure 6 presents data on the amount of backlog processed per fiscal quarter for the 2017–2018, 2018–2019 and 2019–2020 fiscal years. Data are presented in kilometres.

| 2017–2018 | 2018–2019 | 2019–2020 |

|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 |

| 0.12 | 0.41 | 0.25 | 0.47 | 0.28 | 0.4 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.2 |

Interviewees were concerned about the fact that the material in the backlog is not available to researchers and about the risks to the material (such as obsolescence of digital material and carriers, unknown physical condition of other formats). However, they acknowledged that the ability to address the backlog is resource-dependent and that they have been experiencing budgetary pressures. They also acknowledged the need for a planned approach for dealing with the backlog.

Finding 10: There are measures in place to manage the backlog. However, those vary by division and by team, and there is no unified strategy for the Branch as a whole.

Senior management explained that the main mechanism for dealing with the backlog was through special projects, which were impacted by past budgetary and FTEs reductions. Consequently, the backlog projects became largely dependent on the investment of additional resources. Because such resources were unstable and at times unavailable, it was difficult for the divisions to sustain the effort required to address the backlog issue. Current efforts to reduce the backlog are small-scale, and on an annual basis taking into account available FTEs and financial resources. This allows for a small portion of the backlog to be addressed as part of the overall processing. Senior management estimates that, on average, 5%–10% of the backlog is handled that way. The approach used by senior management includes the following actions:

- prioritizing the processing of relevant backlog material when preparing a commemorative event or when there is a research inquiry

- not acquiring more material than can be processed within 1 to 3 fiscal years

- not processing material acquired prior to 1945

- making it mandatory that material acquired in a fiscal year be processed within the same year.

Managers have varied practices for addressing the backlog in their sections according to the nature of the work being performed. Some process the backlog and new acquisitions simultaneously; others have dedicated resources exclusively to dealing with the backlog; and some have put in place a backlog reduction plan. The main issue identified by the managers in dealing with the backlog is the absence of a targeted and strategic approach for the directorate as a whole, lack of proper prioritization, and insufficient FTEs. In some cases, lack of specialized FTEs was also a factor. Interviewees also indicated that there are some technical issues related to the backlog, such as difficulties tracing the donor due to the amount of time elapsed since the material was first acquired.

The document review indicated that, over the past five years, the backlog was discussed sporadically at the Chief Operating Officer’sFootnote 14 Senior Management Team (COO-SMT) meetings in terms of approach, governance and financing. However, formal monitoring reports on the state and reduction of the backlog were not presented.

In 2016, a working group on LAC’s backlogs was created. Its mandate was to coordinate the execution of backlog reduction initiatives related to arrangement, description, processing, preservation and access activities. In addition, the working group was tasked with the following:

- developing a strategic approach for coordinated backlog reduction,

- monitoring backlog reduction initiatives, and

- reporting on a quarterly basis on progress made.Footnote 15

The documentation relating to the working group indicated that it had decided to concentrate its efforts on developing a strategic plan for the management of the processing and description backlog of LAC’s collections. The purpose of the plan was to progressively reduce the backlog by 2022—the anticipated opening of the second Gatineau Preservation Centre (G2). The plan was supposed to identify the specific strategy each directorate would follow over the next five fiscal years.Footnote 16 However, the working group’s activities appear to have stopped in 2017, and the documentation does not indicate whether the plan was actually developed, approved or implemented. LPA management indicated that the funding for the working group was redirected to other sector priorities in 2017.

5. Conclusion

The processing component of the Acquisition and Processing of Private Archives Program (PPAP) is performing well. The program has updated some of its policy instruments and procedures and has taken measures to improve its operations. However, it still needs to address a number of issues, such as revising and updating the rest of its internal policy instruments; clarifying roles and responsibilities; and improving the communication of changes to staff.

Despite the fact that processing policy instruments are not used and applied equally, and that the processing workflow is not functioning in an optimal way, the program component has made good progress in achieving its results. For the most part, the performance targets for processing private archival material are met. Furthermore, the amount of unprocessed material in proportion to total LPA holdings is fairly low, and measures have been taken to address the issue. However, this material remains inaccessible to Canadians, and its long-term preservation is at risk. Sustained effort is needed to ensure that the backlog is processed consistently and remains at a manageable level.

The evaluation results provide LPA management with an opportunity to make adjustments to the processing component of the PPAP in order to improve its performance and the attainment of results.

6. Recommendations

The following are the recommendations to the program management:

Awareness and application of policies, procedures and service standards

- Ensure that policy instruments related to private archives processing are up to date, and implement measures for ongoing communication of any updates or changes to staff;

- Ensure that the processing workflow is documented and communicated to staff;

Efficiency

- Implement a mechanism whereby managers are consulted before archival staff are asked to participate in other institutional activities; and

- Establish and communicate an operational plan to enable staff to better prioritize their work activities.

Appendix A: Management Response and Action Plan

Appendix A: Management Response and Action Plan

| Evaluation Recommendation | Management Response to Recommendations | Action to be Taken | Anticipated Completion Date | Lead |

|---|

|

Recommendation 1: Ensure that policy instruments related to private archives processing are up to date, and implement measures for ongoing communication of any updates or changes to staff | Agree | The review and updating of policy instruments related to processing will be added to the private archives’ three-year operational policy renewal plan | FY 20–21: Determine which policy instruments to review / update and include in three-year policy renewal plan Review the LAC Archival Collection Management Reference Manual FY 21–22: Review / update / develop two additional instruments, and determine ongoing policy instrument renewal needs and add them to the overall renewal plan | Director, Social Life and Culture Director, Science and Governance |

|

Recommendation 2: Ensure that the processing workflow is documented and communicated to staff | Agree | The workflow will be updated following consultation with archival and quality assurance / control teams, and communicated to all private archives staff via email, with links to the workflow | FY 20–21 | Director, Social Life and Culture Director, Science and Governance |

|

Recommendation 3: Implement a mechanism whereby managers are consulted before archival staff are asked to participate in other institutional activities | Agree | A mechanism will be established and communicated to the DGs in Operations and Communications, and to all private archives staff | FY 20–21 | DG, Archives Branch |

|

Recommendation 4: Establish and communicate an operational plan to enable staff to better prioritize their work activities | Agree | An operational plan for processing projects in private archives will be established, monitored quarterly, and updated annually, with targets established in staff work plans Most processing is currently on hold due to COVID-19. An initial plan will be developed for priority projects identified for Phase II return to work | FY 20–21: initial plan for priority projects for phase II return to work FY 21–22: full operational plan for private archives processing in place | DG, Archives Branch (approvals) Director, Social Life and Culture (implementation)

Director, Science and Governance (implementation) |

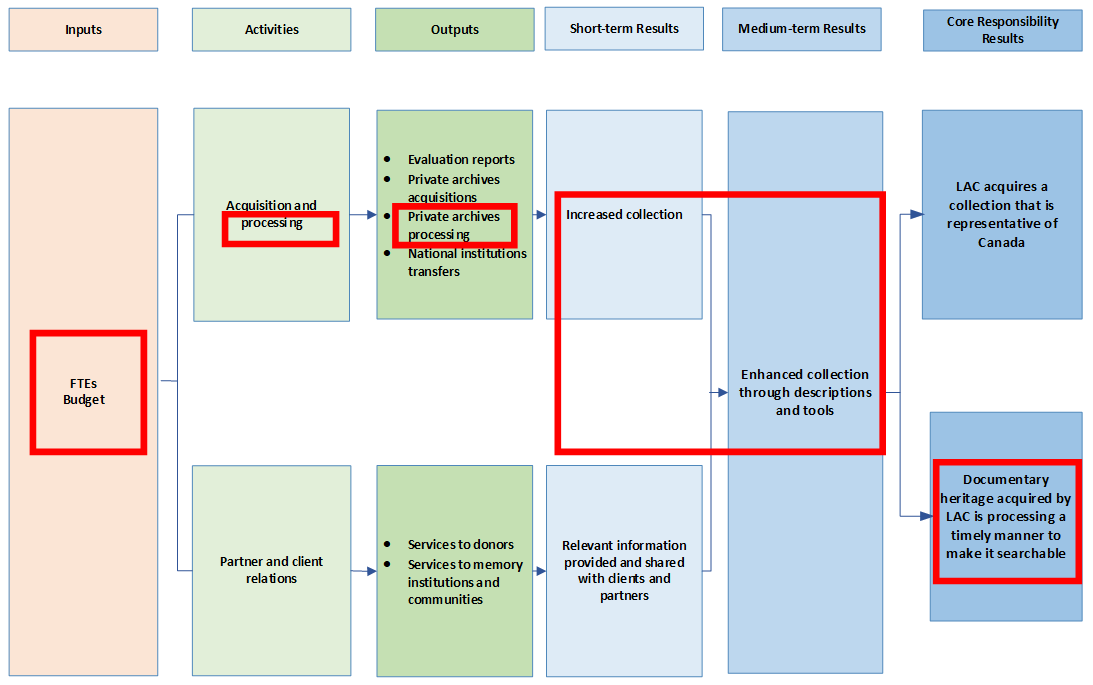

Appendix B: Logic Model for the Acquisition and Processing of Private Archives Program

Appendix B - text version

The diagram presents the logic model for the Acquisition and Processing of Private Archives Program. It depicts the connections between the program’s inputs, activities, outputs, short-term results, medium-term results, and core responsibilities results. The evaluation focused on the activities, outputs and results related to processing.

Inputs: full-time equivalents (FTEs); budget

Activities: acquisition and processing; partner and client relations

Outputs: evaluation reports, private-archives acquisitions, private-archives processing, national institutions transfers; services to donors; services to memory institutions and communities

Short-term results: increased size of collection; relevant information provided and shared with clients and partners

Medium-term results: enhanced collection through description and tools

Core responsibility results: LAC acquires collection that is representative of Canada; documentary heritage acquired by LAC is processed in a timely manner to make it searchable

Appendix C: Performance Measurement Strategy

| Key activities | Logic model element | Indicator | Definition/Source | Data collection frequency | Responsible for data collection |

|---|

| Outputs |

|---|

| Acquisition and processing | Private archives processing | Number of textual containers processed | Total number of 30 cm archival containers processed (discoverable) and sent to Preservation Branch annually or discarded Administrative data | Quarterly | Director General, Archives |

| N/A | Documentary heritage acquired and processed (former PMF) | Volume of acquisitions:

# of private acquisitions.

Volume of processing:

# of private heritage processed | Involves the establishment of preliminary intellectual and physical control of acquired and processed documentary heritage. | Monthly | All acquisition teams, Evaluation and Acquisitions Branch [(EAB) (former)] |

| Short-term results |

|---|

| Acquisition and processing | Increased collection | Percentage of acquired collection aligned with LAC acquisition areas | The number of LAC acquisitions aligned to areas (indicated in the Private Archives Acquisition Orientation 2019-2024) divided by the number of acquired collections (number of acquired fonds by LAC within the fiscal year) Administrative data | Quarterly | Director General, Archives |

| N/A | LAC acquires documentary heritage effectively. (former PMF | Average time required to complete the processing of documentary resources (former PMF) | Evaluation and processing of documentary heritage ensures that collection items are discoverable and comply with established service standards. The indicators measure the compliance of evaluation and processing activities with established service standards | Comparison against targets and baseline Once or twice a year | Manager Project Management Office, EAB (former) |

| Medium-term results |

|---|

| Acquisition and processing | Enhanced collection through descriptions and tools | Number of descriptions | Descriptive records at all levels created or updated in our MIKAN, MISACS databases | Quarterly | Director General, Archives |

| N/A | LAC collection is representative of, and relevant to, Canadian Society (former PMS) | Compliance with evaluation and acquisition policies and strategies (former PMS) | Compliance with evaluation and acquisition policies and standards ensures that acquisition decisions are objective and policy driven (former PMS) | 95% of acquisition decisions conform with the Evaluation and Acquisition Policy Framework

Annually (former PMS) | Manager Project Management Office, EAB (former) |

| Core responsibility (ultimate) results |

|---|

| N/A | Documentary heritage acquired by LAC is processed in a timely manner to make it searchable | Percentage of private archives processed in keeping with service standards | Number of Private Archives processed within service standards during the fiscal year divided by the total number of Private Archives processed during the fiscal year Administrative data | Annually | Director General, Archives |

Appendix D: Factors Contributing to Processing Delays

Appendix D - text version

The graph presents data on the factors that contribute to processing delays and the frequency at which employees experience each factor.

| | All the time | Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | Not applicable |

|---|

| Order of the material | 4 | 19 | 48 | 19 | 4 | 0 |

|---|

| Physical condition of the material | 0 | 19 | 52 | 28 | 0 | 0 |

|---|

| Volume / extent of the material | 15 | 33 | 33 | 19 | 0 | 0 |

|---|

| Complexity of the material | 15 | 43 | 24 | 19 | 0 | 0 |

|---|

| Approvals | 0 | 33 | 38 | 24 | 4 | 0 |

|---|

| Unavailability of archival supplies | 0 | 9 | 48 | 38 | 4 | 0 |

|---|

| Coordination with the Physical Control team | 4 | 28 | 43 | 19 | 4 | 0 |

|---|

| Coordination with the Quality Assurance team | 19 | 48 | 24 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

|---|

| Answering special reference questions | 28 | 15 | 15 | 24 | 15 | 4 |

|---|

| Assisting with the preparation of visits | 15 | 9 | 19 | 19 | 24 | 15 |

|---|

| Assisting with the preparation of exhibitions | 19 | 9 | 4 | 28 | 24 | 15 |

|---|

| Responding to special requests from senior management | 9 | 24 | 33 | 19 | 15 | 0 |

|---|

| Other | 15 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 19 |

|---|

Appendix E: Private Archives Processing Workflow

Appendix E - text version

The diagram presents the activities associated with each phase of the private archives processing workflow.

Note: This chart was created from the LAC Archival Collection Management Reference Manual.

Appendix F: Bibliography

Bachli, Kelley, et al. (2012) Guidelines for Efficient Archival Processing in the University of California Libraries.

Canadian Council of Archives, Rules for Archival Description,

http://www.cdncouncilarchives.ca/archdesrules.html, retrieved May 2020.

Conway, Martha O’Hara (2011) Taking Stock and Making Hay: Archival Collections Assessment, OCLC Research.

Crowe, Stephanie H., and Spilman, Karen (2010) MPLP @ 5: More Access, Less

Backlog?

, Journal of Archival Organization, 8:2

Greene, Mark A., and Meissner, Dennis (2005) More Product, Less Process: Revamping Traditional Archival Processing,

The American Archivist, Volume 68, Issue 2 (Fall/Winter).

Greene, Mark A. (2010) MPLP: It’s Not Just for Processing Anymore,

The American Archivist, Volume 73, Issue 1 (Spring/Summer).

Library and Archives Canada (2016) Access Policy Framework.

Library and Archives Canada, Archival Collection Management Reference Manual.

Library and Archives Canada, Departmental Performance Report (DPR) 2015–2016.

Library and Archives Canada, Departmental Performance Report (DPR) 2016–2017.

Library and Archives Canada, Departmental Performance Report (DPR) 2017–2018.

Library and Archives Canada, Departmental Performance Report (DPR) 2018–2019.

Library and Archives Canada, Examining our Archival Description Practices: Current and Recent Initiatives. Presentation to SMT, January 2017.

Library and Archives Canada (2016) Guideline on Arrangement and Description for Private Archives.

Library and Archives Canada (2013) Policy on Making Holdings Available.

Library and Archives Canada (2013) Policy on Making Holdings Discoverable.

Library and Archives Canada, Vers un Plan de gestion stratégique des arrérages de traitement et description des collections de BAC. Présentée au Comité de gestion du Secteur des opérations, 11 janvier 2017.

Library and Archives Canada (2015) Working Group on Selection, Arrangement and Description of Private Archives: Finding Efficiencies [report].

Novak – Gustainis, Emily R. (2012) Processing Workflow Analysis for Special Collections: The Center for the History of Medicine, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine as Case Study,

RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage, Volume 12, Issue 2.

Oestreicher, Cheryl. (2013) Personal Papers and MPLP: Strategies and Techniques,

Archivaria, 76

University of Maryland Libraries College Park, Maryland (2009) Processing Manual for Archival and Manuscript Collections, last revised 09/2011.